Not being a frequent visitor to the Manawatu region, I was rather astounded to discover this relic. Just a few minutes south-east of Palmerston North alongside SH56, these are the remains of the longest suspension bridge in New Zealand, the Opiki Toll Bridge.

One hundred years ago and more, the soggy swamplands around the Manawatu River were found to be ideal for growing flax. Flax is one of New Zealand’s most notable native plants, and early Maori found a myriad of uses for it once the green surface material was scraped away with a sharp shell or stone. Baskets, mats, fishing nets, footwear and ropes were all adeptly woven, mostly by the womenfolk. With the arrival of both European settlers and the industrial age, word soon spread of the strength and durability of this hardy species. Farmers went into the business of growing it – it was appealingly low-maintenance – and entrepreneurs and engineers built mills to process the leaves. Flax mills became a growth industry (by 1870 there were 161 of them nationwide), and Manawatu was the flax capital, home to several mills, including the largest of all – the Miranui. The riverside Makerua Swamp, 14,500 acres of it, produced nearly 70% of NZ’s flax product, and it was exported by the ton to Australia and Britain.

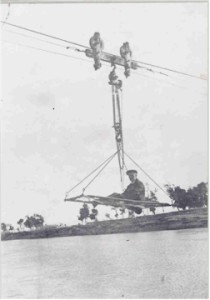

One problem the local Manawatu industry faced was the river itself – the nearest railway line was on the other side! Initially, this was overcome with a handful of flying fox contraptions which could be slowly winched across, or a several-mile detour through swampy roads with horse and cart. Demand for flax was at an all time high, but orders simply couldn’t be delivered fast enough. Frustrated by this logistical bottleneck, and riding a wave of success, the owners of the Tane Hemp Company came up with the funds to build a bridge. Originally named the Tane Swing Bridge, it was completed in 1918.

Designed by Joseph Dawson, the new suspension bridge spanned 155 metres. It was suspended between two reinforced concrete towers that were 14.6 metres tall. The towers held 16 cables (8 a side) which passed over rollers that topped each tower. These cables were obtained from the Waihi gold mines and had been tested to hold a weight of approximately 50 tons. They were attached to long, bronzed-steel rods that were anchored into massive concrete blocks buried 5 metres deep. The decking was 8 x 3 inch planks of black beech timber. Amazingly, all the iron work on the bridge was done on-site by one man, Tane Mill staff blacksmith Ernest Henderson.

Unfortunately for the Tane Mill, by the time their bridge was finished the industry was already in a post-war slump. Flax prices had fallen to less than half their wartime boom, and the plantations were afflicted by Yellow Leaf, a then-unknown disease which mystified the farmers and eluded their efforts to eradicate, cure or contain it. The Tane Hemp Company sank into liquidation in 1922, with one of the shareholders buying out the remaining stock. Hugh Akers was now the proud owner of a colossal, low mileage, suspension bridge.

He soon found his new aquisition to be somewhat of a burden, what with locals constantly asking to use his private road and bridge. He eventually decided to open it to the public, offsetting the upkeep, insurance, and management costs by imposing a toll charge. Railway tracks used for shuttling flax shipments to Rangiotu station were pulled up, and he had a house built on the Opiki (SH56) side to accommodate a toll keeper. The bridge was renamed the Opiki Toll Bridge in early 1926, and the wooden-decked, single-lane landmark served its community for a further 44 years.

With road traffic increasing exponentially a modern concrete bridge was finally constructed in 1969, just downstream of the old one. For safety reasons the beech planking was removed, and the structure was officially decommissioned in November of that year. The brick towers and most of the cables remain, as does the chimney from the old Tane Mill, skeletal spectres in an unsullied hinterland. These have very recently become Class 1 Heritage Sites.